There are several ways to biomechanically represent the spine during the golf swing using motion capture technology, here are two examples, the rigid spine method and the two-segment spine method.

Rigid Spine Method

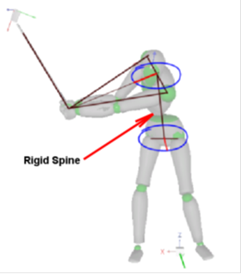

The rigid spine method uses markers or sensors to define the left and right shoulders plus the right and left hips. A point mid-way between them is calculated and these two points are joined with a straight line. The spine is represented in this method by a rigid line between the hips and shoulders. Several current optical motion analysis systems use this method to define a “virtual” spine. AMM3D also has this calculation available when selected.

| Figure 1. Rigid Spine. Here the spine is defined by a single line drawn between a point mid-hips and another point mid-shoulders. This spine is rigid and does not flex with respect to its ends. |

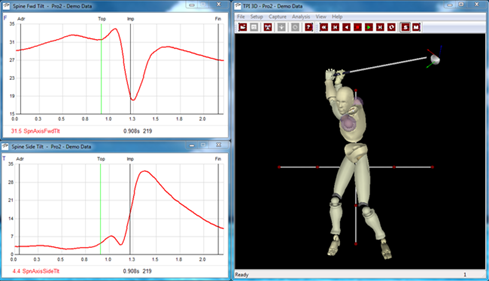

When we chose to look at the data from the rigid spine calculations in the AMM3D system we get two graphs; forward-backward tilt and side-to-side tilt. Figure 2 has a graph to show each. This is from the “Pro2” demo swing, showing the golfer at top of backswing. These two calculations are global measurements, measured with respect to vertical, from a front and side view. This is similar to what you do when analyzing video. They are called projected angles.

| Figure 2. Rigid Spine Tilt Graphs from AMM3D. Spine Axis Forward Tilt and Spine Axis Side Tilt. When the swing is animated the green vertical line on each graph moves synchronously with the robot model. Any set of graphs can be chosen and saved as a specific layout. In this example the robot is stopped at the top and the green lines show the spine tilt values for each curve at this point in the swing. |

In Figure 2, the top graph is Spine Axis Forward Tilt and the bottom graph is Spine Axis Side Tilt. The green vertical lines show the pro’s values at top, 31.5 degrees forward and 4.4 degrees sideways to trail side respectively, and the image shows the golfer’s body position. The AMM system can step through or play the whole swing and give the values from the graph at the same time for all points in the swing.

Two-Segment Spine Method

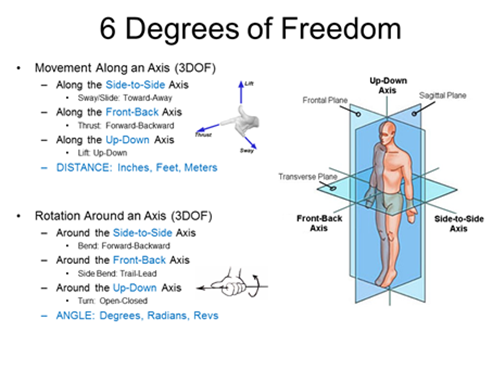

Another method of spine representation, AMM3D’s primary method, is to use a six-degree-of-freedom (6DOF) definition for the thorax (ribcage) and the pelvis. A local coordinate system is positioned internally for each segment and then anatomically aligned with its segment. This coordinate system moves with the segment to which it belongs. What this means is that a 6DOF sensor is used to define the complete motion of each segment, including, the three positional degrees of freedom; sway, thrust and lift, plus the three angular degrees of freedom; bend, side-bend and turn. Figure 3 explains the six-degrees-of-freedom of motion as related to the golf swing.

Figure 3. Six-Degrees-Of-Freedom of motion as related to the golf swing.

The spine is defined as the relative motion between the pelvis segment and the thorax segment. The strength of this method is that we get to see the relative motion of the ribcage with respect to the pelvis. The rigid spine method doesn’t allow us to do because it assumes there is none.

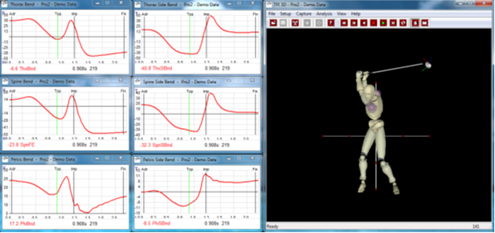

In Figure 4 below, you can see that the thorax (ribcage) and the pelvis are actually modeled as two separate segments capable of independent motion, at least as much as is physically possible. Of course this is still a simplification of true spine motion since the spine has a joint at each vertebra, but at least we can now see how both the global and relative motion of the pelvis and ribcage contribute to the efficiency and power in the swing.

| Figure 4. AMM3D image of the golfer at top of backswing. Notice the thorax (ribcage) and pelvis are two separate segments capable of their own independent 6DOF motion, at least as much as is physically possible. |

With the two-segment spine method we get much more information than with the rigid spine method. We get forward and sideways bend for pelvis, spine and thorax; six graphs as shown in Figure 5.

| Figure 5. Two-Segment Spine Graphs from AMM3D. This figure shows graphs for all six angles; pelvis, spine, thorax, bends and side bends. The golfer is stopped at the top and the vertical green lines in each graph show the parameter values for each curve. |

The forward bend angle of a segment is the angle between a front-back anatomical axis and the horizontal plane. The side bend angle of a segment is the angle between a side-to-side anatomical axis and the horizontal plane. The anatomical reference axes move with the segment during the swing.

The spine angles are relative angles calculated from the thorax with respect to the pelvis. Note that if you try to calculate the spine angle from the difference between the pelvis and thorax angles you may not get exactly the same answer as seen in the graphs above. That is because in 3D when there are three simultaneous angles present they do not simply add up, specific 3D relative joint calculations must be used.

This method is powerful when looking at the risk of injury in the swing, for example we can see if the following are evident:

- C or S posture at address,

- Reverse spine angle at top,

- Pelvic anterior/posterior stretch-shorten in early downswing,

- Excessive spine right side around impact (allied information to the “crunch factor”), and

- Reverse C and excessive side bend at finish.

These risk characteristics will be discussed in subsequent articles. All of these factors when performed excessively and repetitively can lead to lower back injury. Dr. Peter Mackay and I do AMM3D analysis sessions in San Diego on the weekends and we are tending to see a lot of these factors used by our young high school and college players. The truth is several of these “faults” do actually increase power and speed in the swing and so are popular. Unfortunately our young golfers are generally not strong enough to support these vigorous aggressive body positions and actions. We are now avidly trying to point out to our golfers that they are “players at risk” when performing these moves. We believe they have two good choices and one bad choice. The good choices are to modify technique to eliminate these dangerous moves and to get stronger by undertaking an effective strength and conditioning program. The bad choice would be to continue hitting over 300yds but with injury lurking in the future.

The AMM3D system can help with modifying technique by measuring and displaying dangerous values, which are highlighted in red when compared to the TPI pro databases. Then, using built in real-time biofeedback, we can help our golfers train the new correct movements. In follow up sessions we can again measure to see if we are achieving our goals.

© Phil Cheetham, 2013